Two months ago, Tesla launched its Model D. Not quite a new car, not even a refresh, but the webs went wild. The Model D sports an extra electric motor, and a sensor package. Any other automaker, and such non-news would not even elicit a yawn from the press, save for a few snarky blogs that would torture the maker for not delivering the software for the hardware. Come to think of it, no automaker would dare to deliver hardware sans software, for fear of getting their derrieres handed to them. Tesla is unlike any automaker. As a Silicon Valley company, Tesla has marketing rights to vapor ware. The Model D was feted like the second coming of the Model T, and it was pronounced as equally, if not more disruptive to the industry than the mass-produced Ford.

Musk’s acolytes expected a self-driving car from Tesla, and they were given what they wanted to hear: The Autopilot. The official feature-list of The Autopilot is surprisingly feature-less. Currently, it offers exactly nothing, except for some “exciting long-term possibilities. Imagine having …” Then, a list of imaginary stuff follows that would have made Ford/Microsoft’s derided Sync system look worse. The listed exciting long-term possibilities, even those, are completely devoid of anything even remotely autopiloting.

The media came to Musk’s assistance, and made the missing Autopilot up. The members of the gadget press quickly reduced The Autopilot to a “smart lane-change system which will automatically move across a lane when you hit the blinker,” as Slashgear wrote. Not quite an Autopilot, but hey, good enough.

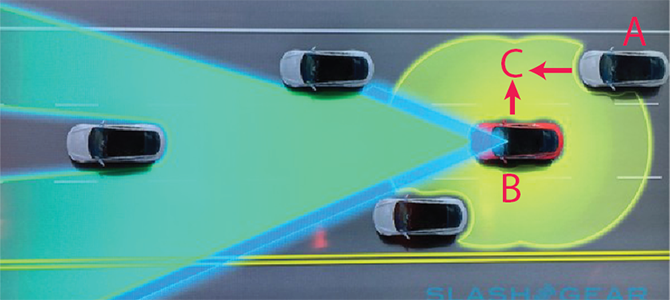

Trouble is: You won’t find the game changing lane-changer in Tesla’s Model D description, not even under “long-term possibilities.” Smart move on Tesla’s part, because it’s not going to happen. The hardware package renders the presumptive Autopilot blind.

The Model D hardware package comes, says Tesla, with “a forward radar, 12 long-range ultrasonic sensors positioned to sense 16 feet around the car in every direction at all speeds, and a forward-looking camera.” Sorry. For a safe lane change, we must look sideways (any car there?) and behind (any car coming down the lane at high speed?) Even an aspiring geek knows: Radar and camera look forward, they are blind in other directions. Those puny ultrasonic sensors (think 1978 vintage Polaroid SX-70, if you were already alive) are barely enough to be helpful in a parking lot. If an automatic lane-changer relies on ultrasonics that develop range anxiety after 4 meters, it will turn into a serial killer of cars in the other lane.

The drawing, helpfully provided by Slashgear, and annotated by the Daily Kanban, illustrates the technical dilemma: Car A, recognized far too late by car B’s rectally challenged sensor, joins car B in unholy matrimony, and bangs it in position C. Now picture the cars currently to the right of your computer screen, approaching at 80 mph. If all that covers my ass is a sensor that relies on chirping bat noises, I would not want to own that car company.

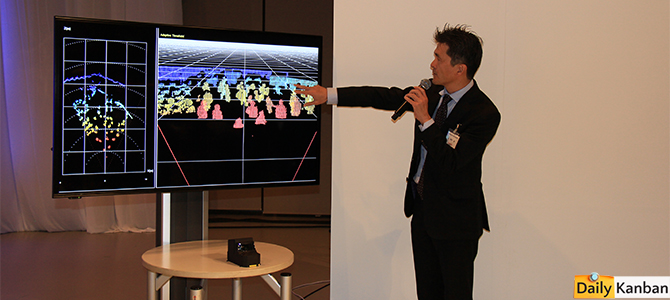

In case you don’t know enough yourself about the technical details of the attendant sensoric deprivation, please don’t take my word for it. Ideally, Tesla should be confronted with these questions, however, based on past experience, I won’t even ask. Instead, I took the matter to Toyota, an early venture supporter of Tesla, and still a TSLA stockkolder, albeit at a slightly reduced rate. The opportunity arose when Toyota’s top intelligent vehicle engineers showed off current and future intelligent drive hardware – with software. Toyota’s droll engineers answer any question thrown at them, so here it goes: What sensor package is needed for an automatic lane-changer?

“If you just go straight on, and you are not changing lanes, then the one sensor going forward, camera and radar, is good enough,” says Ken Koibuchi, General Manager of Intelligent Vehicle Development at Toyota. “When it comes to lane changes, we have to look in all directions. Otherwise, the system can’t make reliable decisions. You absolutely need radar in all directions for changing lanes. You can have a number of cameras installed in the car, but they won’t help you for distance with their wide angle lens, their resolution is very poor. You need to cover long distances, and a wide field of view at the same time.”

It’s a bit much all at once, but I kind of follow. And then, Koibuchi drops the other shoe: “Currently, there is no radar on the market that can achieve that with the required form factor and cost.” It’s the polite Japanese version of “are you kidding me?”

At this point, you will probably interject that forward-looking sensors for more or less autonomous cruise control can hardly be called earth shattering. Absolutely right you are. No disruptive technology there. Having been available in high end cars for many years, components now have come down in price and package size allowing them to be fitted in run-of-the-mill cars like the Volkswagen Golf, the Hyundai Sonata, the Subaru Forester, even a Model D. Toyota is rolling out the technology across its whole vast range of models. In doing so, Toyota uses two sensor packages.

Their lower cost Toyota Safety Sense C package uses laser radar combined with a camera. It delivers a Pre-Collision System (PCS) to help prevent and mitigate collisions; Lane Departure Alert (LDA) helps prevent vehicles from departing from their lanes; and Automatic High Beam (AHB) helps ensure optimal forward visibility during nighttime driving. (Copypaste from Toyota’s on-line propaganda, as you can tell.)

Toyota’s higher end Safety Sense P (as in pricey?) package uses millimeter radar combined with a camera. In addition to all what can be done by the cheaper system, the premium-priced P package provides a Pre-Collision System that is refined enough to detect pedestrians in addition to vehicles, and a radar cruise control that keeps its distance to the car in front.

Toyota is confident enough in its technology to allow me to test it. As hard as I try, I am unable to crash the car into a wall, or a pedestrian dummy that walks in front of my car. Automakers can buy both sensor packages off the shelf. The supplier of the cheaper package is Germany’s Continental, the tire-manufacturer-turned-high-advanced-component-supplier. The pricier P system can be ordered from Denso, the parts maker in Toyota’s keiretsu. Tesla goes the same off-the-shelf route when it comes to components.

“Bosch is our supplier of the long-range ultrasonics, and the RADAR,” Elon Musk told Germany’s Auto BILD in an interview. “We do the camera assembly using a mobileye chip, but all of the software for integrating that, we do at Tesla.”

Big HOWEVER: Those hardware packages are not good enough to allow the car to change lanes on its own. Not by a long shot. Even if they could, the software will be the biggest challenge. Our eyes can recognize obstacles reliably. How often does the software in our brains fail?

“I cannot say at this moment that automated steering is reliable enough for commercialization,” says a spiky-haired Koibuchi in polite Japanese. Translation: Fuhgeddaboutit.

I am shown two Lexus cars. One of them, an LS, sports the massive roof-mounted array of assorted gizmos, complete with rotating coffee can radar, video cameras, GPS, and other sensors. By now familiar giveaway: Here comes an experimental autonomous car, step aside. Next to it is a normal looking Lexus GS that is everything but normal. It comes with most of the coffee-can technology in an unobtrusive under-the-rear-view-mirror package. Its millimeter radar has its accuracy down to less than an inch (try that with ultrasonic).

“It can even recognize the shape of a person,” says Koibuchi. I wave my arm. The RADAR catches me waving.

The system has a minor drawback. It exists only in Toyota’s lab in Higashi-Fuji. Toyota hasn’t found a supplier yet who can make the thing at a price and package size needed for large-scale rollout. “We are talking to everybody,” says Koibuchi. Asked whether that would be the highly advanced Japanese companies, Koibuchi makes a dismissive wave, and says:

“Not at all! Military sensor technology is much more advanced in the U.S.! Europe has very good camera technology.” Saving lives with killer technology.

Oh, one more thing: “We also need high performance mapping,” Koibuchi adds. “I am not talking about navigation, that is relatively easy. For automatic steering, maps must highly accurate. Road conditions don’t stay the same. We need new map suppliers for that.” So, you are talking to Google then? A whole shoestore drops:

“No, we haven’t had any conversations with Google.”

Even if and when that super sensor is released into the wild, and if and when the high performance maps have been made, the car won’t change lanes on its own just yet. To look rearward and sideways as needed to avoid sideswipes and rear-enders, the car would need at least three of those unobtainable sensors, I am told. And then, they would need software reliable enough to convince Toyota that the lives in your car and in the cars behind you can be put into the digits of computers.

Toyota was accused that their cars would drive themselves. It took NASA to disprove the accusation. Nevertheless, the witch-hunt did cost Toyota more than $4 billion at last count, and the wheels of alleged justice are still grinding. No telling what will happen when the cars really drive themselves. Nobody has an answer to this. Even if some day all challenges of autonomous driving have been mastered, as long as no answers have been found, it will be the lawyers who will stop the tech from taking to the streets.

That reminds me: Last year, I was shown a car that did not just stop when a pedestrian dummy walked in front of it. The car recognized the dummy, and the car would steer around it, automatically. An autonomous lifesaver. At the demo a year ago, a crazy driver (name on request) intentionally steered into the dummy, and killed it. I tried to sell the picture to Toyota for a lot of money, and for more than a year. Having found no takers, here it is. Imagine what would have happened if the dummy would have been for real. “The car drove itself, members of the jury, and we can prove it!”

A year later, no more self-steering cars. They aren’t ready. After 2020, maybe, probably not. The tech is there, but nobody in his right mind will let those autonomous cars run wild without adult supervision. “As we introduce new technologies, there is a risk for Toyota that we have to take responsibility for any failures,” says Moritaka Yoshida, who joins the discussion. He is Toyota’s chief safety technology officer, and after his company was pilloried for ghosts in the machines, and after feet were held to the fire, Yoshida-san has developed a healthy respect for the ghost-busters.

Nevertheless, Yoshida knows he needs the computers, even if they are “sometimes quite temperamentful,” as he says. “There is a limit to reducing fatalities using passive safety alone,” explains the engineer who has been on the job for more than 30 years. The safety cells in Toyota’s cars are as safe as they can get, and “we don’t have any plans to enhance the body structure more than what we have now.” Yoshida’s and his company’s research goes into active safety, into avoiding accidents, or into slowing the car down when an accident becomes unavoidable. For that, sensors and computers are needed. Toyota frames the story as saving lives, not as sparing us the driving.

But, but, what about all those self-driving cars we read about, Yoshida-san, you know, the ones that will imminently upend the car industry?

“If all you want to do is to go from A to B, you won’t need a car at all,” says Yoshida.

And right he is. After the talk, I wave my contact-less SUICA card at the driver-less, fully autonomous Yurikamome line, and half an hour later, I’m at home, haven’t touched a steering wheel.

The future has begun.

P.S.: If that Autopilot changes lanes automatically at the touch of a blinker stalk by, say, one year from now, in a series Model D, I will publicly eat a Tesla baseball hat on Twitter, Facebook and YouTube. How about it, Elon?